| "Freemasonry is deceptive and fraudulent...Its promise is light—its performance is darkness" |

|

The question of Freemasonry and the controversy over its character—whether the fraternity is good or evil—has long been a feature of American life. Since the earliest days of the American republic, politicians, clergymen, and ordinary citizens alike have engaged in vigorous debate and investigation into the virtue, purposes, and meaning of the Masonic Lodge.

For John Quincy Adams, writer, poet, faithful husband, patriot, former Ambassador and Secretary of State, and sixth President of the United States, there was no question. The dispute was firmly settled in his mind. The teachings and practices of Freemasonry, Adams asserted, are detrimental, noxious, and unfortunate. John Quincy Adams was persuaded that the Lodges were a bane to society, evil and Luciferian.

So convinced was Adams of the devilish and negative effects of Freemasonry in the affairs of men that the former President of the United States helped to found the Anti-Mason Political Party. In 1830, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives on the Anti-Mason Party ticket. For years Adams carried on an active and heated literary and speaking campaign against Freemasonry. The classic book we have just reprinted, Letters on Freemasonry, contains important correspondence written by John Quincy Adams on the controversial subject of Freemasonry.

A Sterling Place in History

A brief biographical sketch of John Quincy Adams is in order. His illustrious father, of course, was John Adams, one of America’s most famous and revered founding fathers. While the fortunes of history favored his courageous father, the son, John Quincy also successfully carved out for himself a sterling place in history. As a precocious young man, he traveled and lived years in Europe with his parents and relatives. By age 10 he was already reading Shakespeare and took up a formal education at the distinguished Passy Academy near Paris, France. He went on to master Latin, Greek, French, Dutch, and Spanish languages and studied law. He graduated from Harvard University in 1787 second in his class, with high honors. A brief biographical sketch of John Quincy Adams is in order. His illustrious father, of course, was John Adams, one of America’s most famous and revered founding fathers. While the fortunes of history favored his courageous father, the son, John Quincy also successfully carved out for himself a sterling place in history. As a precocious young man, he traveled and lived years in Europe with his parents and relatives. By age 10 he was already reading Shakespeare and took up a formal education at the distinguished Passy Academy near Paris, France. He went on to master Latin, Greek, French, Dutch, and Spanish languages and studied law. He graduated from Harvard University in 1787 second in his class, with high honors.

After serving in succession as Minister to Great Britain, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State, Adams ascended to the presidency of the U.S. following the election of 1824. Among his achievements as chief executive were extended roadways and the construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Earlier, as Secretary of State he helped formulate the Monroe Doctrine, and as an U.S. Representative, Adams was responsible for the founding of the Smithsonian Institution.

John Quincy Adams was neither a social back-slapper nor a "smooth operator" type of politician. He was known as quiet, sober, plainspoken, and serious, and he was dedicated to the improvement of his country.

Interestingly, Adams recognized and was keenly aware of his uncompromising nature and less than charismatic personality. He wrote in his diary, "I am a man of reserved, cold, austere, and forbidding manners...My political adversaries say gloomy and unsocial."

Adams lamented this "defect in my character" and remarked "I have not the pliability to reform it."

"I never was and never shall be what is commonly termed a popular man," Adams concluded. "I have no powers of fascination; none of the honey..."

Perhaps he had no fascination and honey to attract and influence people, but what John Quincy Adams did have was considerable. He had the respect of his peers, and he earned the admiration of the people. Adams was strong in opinion, single-minded, determined, honest and highly intelligent. Though he checked his temper, he did not hesitate to stand up for what he perceived as injustice, unrighteousness, and wrongdoing.

Adams never quit fighting for the abolition of slavery. In 1841, in the Amistad case, he argued successfully before the Supreme Court to win freedom for black slaves who had engaged in a mutiny against oppressive white slavemasters aboard the Spanish ship Amistad.

"A Devout Christian"

No doubt it was his sense of duty as a Christian which so compelled Adams to fiercely battle against injustice and prejudice and to support freedom, liberty, and human rights. The authors of The Complete Book of the Presidents note that John Quincy Adams was a devout Christian. They add:

|

"He attended church regularly and often worshipped twice on Sunday. All his life before retiring each night, he recited...prayer...In the morning he invariably read several chapters of the Bible before starting his day." |

Adams occasionally wrote of his faith, testifying: "I have at all times been a sincere believer in the existence of a Supreme Creator of the world...and of the divine mission of the Crucified Savior, proclaiming...‘Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.’"

On his deathbed on February 23, 1848, realizing his grave condition following a massive stroke, Adams simply said, "This is the end of earth. I am content," and he gave his last breath.

Intense Desire to Expose the Masonic Lodge

It was, I am convinced, his strong Christian faith and religious convictions, as well as his thirst for justice and his common sense, that ignited the intense desire in Adams not only to expose the falsehoods inherent in Freemasonry, but also his desire to discourage men of good will from joining or participating in what he clearly saw as an unethical, unscriptural, and unholy secret society.

If he needed any additional justification, it was the tragic murder of Captain William Morgan in the state of New York in the year 1826 that further heightened Adams’ sense of urgency to warn of the dangers of the Masonic Lodge. Morgan, an ex-Mason, had revealed some of the secrets of the Masons—oaths, handshakes and ritual trappings, etc. In retaliation, he was ritually murdered in a particularly gruesome manner, and his lifeless, mutilated body abandoned in a lake.

The facts of Morgan’s murder were subsequently covered up by lawful authorities, reputed themselves to be Masons. When evidence ensued that the Masonic Society had assisted the culprits responsible for Morgan’s death to elude capture and escape punishment, the event caused a national scandal. Newspapers and periodicals across America—especially those whose publishers and editors were not Masonic initiates and supporters—carried all the gory details of the Morgan affair. Politicians were forced to take sides; some went so far as to found the Anti-Mason political party to elect candidates and enact legislation to overturn what many feared and suspected was the undue influence of the Lodge throughout government and society.

Adams was instrumental in founding this Anti-Mason Party. But politics was only one arena of life in which Adams overtly took on his Masonic opponents. For him this was a holy cause. He set out to investigate and learn all he could about Freemasonry, and in the backwaters of the Morgan affair, there were many former Masons who had renounced their involvement and were willing to share their knowledge.

|

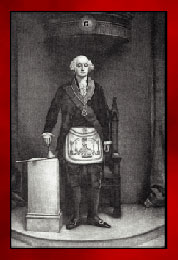

Today, the Masonic Lodges boast of many famous leaders who have been Masons. They claim George Washington as one of their own and point to this famous painting depicting our first President as Worshipful Master of his Lodge. But in Texe Marrs' audiotape exposé, The Masonic Plot Against America (60 minute • $10), Washington himself is quoted as saying he visited the Lodge only once or twice in over 30 years. |

Membership in Lodges Eroding

The significance of John Quincy Adams’ campaign in opposition to Freemasonry is vital. Indeed, the debate regarding the merits—and demerits—of the secret society continues to this day. From its high point in 1959, the number of Master Masons has continued to slide, even though the general male population of the United States has rapidly grown. According to the Masonic Services Association, in 1959 there were 4,103,161 Master Masons in lodges in the U.S.A. By 1997 that number sank to just 2,021,909—and indications are that membership continues to erode.

Why I Oppose The Lodge

It is very possible that the more recent ferocious opposition to the Masonic Lodge in the 1990s is at least partly responsible for this dramatic drop. If so, admitting my own bias, I am glad. I count myself as one of those who oppose Freemasonry.

My reasons are many, though they center mainly on my informed conviction that the Masonic Lodge is unchristian, generally amoral, and decidedly unwholesome. Indeed, I view today’s Free-masonry as a loathsome leftover of the old pagan religions and an unfortunate reminder that a virulent form of occultism and Egyptianism lingers on within the boundaries of these United States.

I readily admit the Lodge is responsible for some worthy humanitarian endeavors, and there are some good men who are Masons. Nevertheless, its origins, nature, rituals, and practices negate whatever noteworthy attributes there are pertaining to Lodge membership.

Masonry Radically Anti-Christian

If Masonry was a negative force detrimental to the spiritual welfare of men in the day of Adams, it is much more so today. Following the great U.S. Civil War (1861-1865), a man named Albert Pike became Sovereign Grand Commander of Scottish Rite Freemasonry. Pike overhauled and revised the lodge rituals, implementing a 33 degree system of initiations that is far more radically anti-Christian and pagan than was previously in place.

Moreover, more recent Masonic leadership has continued to promote a universal theology and other distasteful aspects of Freemasonry which fall, in my opinion, on the dark side.

Tremendous research in this matter by authoritative researchers Ralph Epperson, John Ankerberg, James Wardner, Ed Decker, Bill Schnoebelen, Cathy Burns, Reginald Haupt, James Holly, Jim Shaw, Tom McKenney, Jack Harris, E.M. Storms, and by many others confirms my own findings. Thus, the warnings of John Quincy Adams, if anything, strike with greater clarity and impact today than they did upon their first publication in the nineteenth century.

With this in mind, I consider the writing of John Quincy Adams in the insightful volume, Letters on Freemasonry, remarkably current and a godsend. I heartily recommend this book to every thinking and caring man and woman on earth—and especially to the men who frequent the Masonic Lodge.

Let them read what one of our nation’s most excellent leaders and builders had to say about the Lodge. Then may, they well compare the teachings, rituals, and symbols found behind the Lodge’s closed doors to the open doctrines and marvelous principles prescribed and contained in God’s Holy Word, the Bible.

I believe that, having done so, no true Christian, no earnest seeker of religious truth, will continue in the Masonic Lodge. Surely, a Christian can be a Mason, but if the truth of Christ lies within his heart, that man will not for long remain a Mason.

|